The HSE is reviewing a medical card next week. Its reviewers are going to decide whether they should keep this card in circulation. Though an HSE official as late as March 2021 thought this card belonged to a foster child born in 1960, it has in fact been formally registered to either a Dublin-based GP or a homelessness organisation since 2007.

This card has had a difficult past.

Back in 2013, HSE officials began raising concerns about how this card was being used since it had come into the possession of this Dublin GP, the founder and former chairperson of a homelessness healthcare charity. There was no transparency on the charges being made on the card and there were questions about whether its use was resulting in the HSE being double charged for certain medical procedures. One GP working for the homelessness charity wrote to the HSE in October 2020 to articulate her unease at how “profitable” its use had become over the years.

The lack of transparency on the card was such that the HSE didn’t know until April this year how much had been charged to it.

There has been €22,404,819.52 charged to this single medical card since 2007.

It’s what’s known as a generic medical card. The HSE used to issue these generic cards to organisations such as women’s refuges and homeless hostels housing people with no medical cards. These generic cards were considered an easy way to bill the state for healthcare provision in instances where patients had neither medical cards nor the means to pay. Though the practice of issuing these cards stopped in 2011, there are still around 100 in circulation.

Of those still in use, the majority have relatively low charges made against them. The card with the second-highest charges has recorded a yearly average of €253,203.13 for the same period, 2007-2020.

The HSE had thought this particular card, card number K699982A, with six times as high a figure, was only being used sparingly after the fallout of a 2013 internal memo from the then HSE COO, which had resulted in investigations into serious governance issues with the card.

This medical card was associated with charity Safetynet Primary Care, which provides healthcare to homeless people, Travellers, Roma people and heavy drug users. Internal correspondence shows the HSE considered the charity’s founder, Dr Austin O’Carroll – Irish Paralympian, clinical lead for the Dublin Covid-19 homeless response and 2020 European GP of the year– responsible for it. In late 2013 after O’Carroll had to defend to the HSE charges put on the card, it had been assumed fees billed to it would decrease.

This didn’t happen. Charges continued to increase right through to 2020. Uncertainty over just who controls the card also increased after O’Carroll resigned from Safetynet and founded a new homelessness venture with former colleague Dr Kieran Harkin, in whose name the card is currently registered. O’Carroll’s resignation followed a corporate and clinical governance review of the charity.

“This was new to me,” as an HSE assistant national director put it in a December 2020 email to his colleagues after finally learning who had ultimate responsibility for this medical card.

The review the card faces next week isn’t special. Despite all the uncertainty, the concerns, the €22 million, it’s continued to pass reviews year after year. There aren’t any indications this particular review will be any different.

‘It is very profitable’: Safetynet medical director

Four men stood under an awning outside the Capuchin Day Centre for Homeless People on Bow Street in Dublin 7 at around 10am on a rainy May morning. As they waited in line to receive food parcels inside the centre’s main door, others came, went and knocked on a door at the other end of the centre.

The people knocking on the door at the centre’s tail end were there to see a chiropodist, nurse or dentist in a clinic run by the centre with the Mountjoy Family Practice, which is owned by Austin O’Carroll. The clinic until recently was advertised on Safetynet's website as being affiliated to the charity, which O’Carroll founded but resigned from in 2016.

A clinic run by O’Carroll, in the same homeless centre, which provides healthcare for homeless people, had by late 2020 become “very profitable”, according to current Safetynet medical director Dr Angela Skuce in an October 2020 email to two senior HSE officials.

In Skuce’s email she copied her boss, Fiona O’Reilly, Safetynet’s current general manager. O’Reilly, a PhD and former research partner of O’Carroll, came to Safetynet after O’Carroll’s resignation. O’Reilly today says she doesn’t know why O’Carroll resigned from Safetynet when he did. “I don't think there were reasons for the resignation,” she said.

O’Carroll’s resignation from Safetynet’s board came after the HSE raised serious questions about how the charity was being run. He still however works with the charity today. O'Reilly said O'Carroll is "recognised as a founding member of the organisation and a GP with significant experience and expertise in the area of homelessness", and that Safetynet "works collaboratively with Dr O’Carroll and other healthcare providers in the homeless sector".

After O'Carroll's resignation he has continued to run clinics linked to the charity – the clinic in the Capuchin Centre being one.

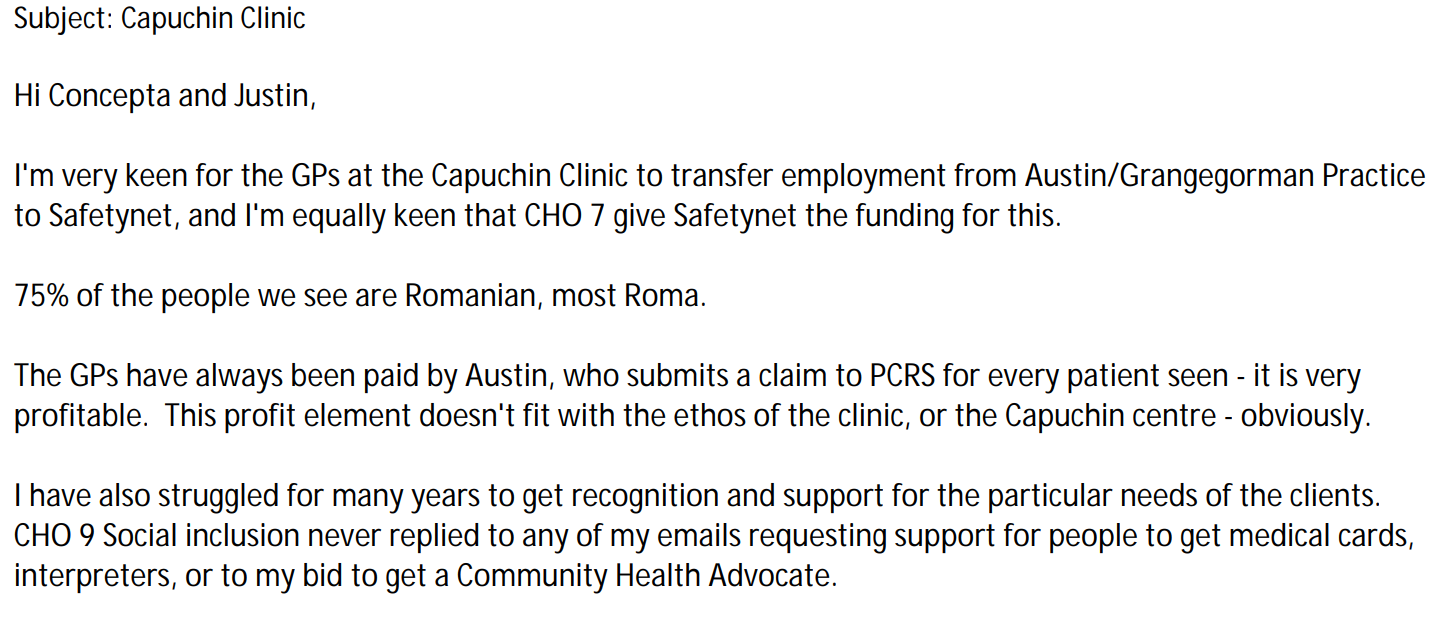

Skuce in her email asked if the HSE would take responsibility for the clinic in the Capuchin Centre from O’Carroll and give it to Safetynet. She wrote that O’Carroll would accept this arrangement and went on to outline why she wanted this.

“The GPs (in the clinic) have always been paid by Austin, who submits a claim… for every patient seen - it is very profitable. This profit element doesn't fit with the ethos of the clinic, or the Capuchin centre - obviously,” wrote Skuce.

In the year Skuce sent her email, a total of €3,321,103.65 was charged to the generic card. The year before, €2,794,807.75 was charged. When asked where the profits referred to by Skuce went, O’Reilly declined to answer and said the clinic, after Skuce’s email to the HSE, moved to a not-for-profit model earlier this year.

The HSE didn’t keep records of the total charges to any of its generic medical cards, such as card number K699982A, until The Ditch asked for a breakdown.

The card itself is formally registered in the name of Dr Kieran Harkin, a former Safetynet colleague and co-founder with O’Carroll of GMQ Medical, a private partnership similar in mission to Safetynet. Figures released to The Ditch by the HSE however put this card in the name of Safetynet and Dr Austin O'Carroll.

It’s worth noting that the charges made to this card are distinct from the general medical services (GMS) fees paid to GPs, typically reported by Irish media each year. GMS fees are paid on the basis of the number of medical card patients seen by GPs in a given year, whereas the fees paid to generic medical cards are entirely separate. O’Carroll is one of the highest paid GMS GPs in the state, with €974,000 including practice support paid to him in 2020. The fees claimed on generic medical card K699982A are however a different matter.

Due to expire 30 September, 2021, generic medical card number K699982A now faces a review on 30 June.

Skuce’s mail, which hinted at profiteering and unaccountability linked to a particular generic medical card, seemed to catch leadership at the HSE unawares. It also, for some involved in the conversation, recalled discussions years previous about the same generic medical card.

The 2014 HSE memo that found no accountability, no contract and possible double charges

The HSE’s Carmel Burke did not want to detract, she wrote, in any way, “on the appropriateness, effectiveness and quality of service provided”, nor the “commitment of the individuals involved with Safetynet”.

She did however want to raise some “governance issues” about this charity.

It was February 2014 and Burke was dealing with an intervention the previous June by the HSE’s then COO Laverne McGuinness. McGuinness had sent a memo to the HSE’s regional directors of operations, voicing her concerns on increased healthcare charges for homeless people, asylum seekers, islanders and some community nursing programmes. This memo triggered something of an audit within the HSE, with different departments either forced or encouraged to look at what they were spending on these services and the fees being billed to organisations like Safetynet.

Burke was the HSE’s primary care reimbursement services head of operations, which meant she had responsibility for paying the primary care providers the HSE contracted – primary care providers like Safetynet and its affiliated GPs.

Sending a memo of her own, Burke outlined her issues with Safetynet and its use of the generic medical card. These issues included:

“No accountability or performance monitoring of service provision at a cost of €0.5 million annually”; “no visibility of a contract… either with Safetynet or more appropriately with the individual participating GPs”; “doctors are providing services to clients who are the registered patients of other doctors and the HSE is paying two doctors for service provision.”

Though the HSE had stopped issuing these generic medical cards in 2011, some remained in circulation, and Burke was well aware of the risks of allowing these cards to remain in the control of organisations like Safetynet.

“When we centralised in 2012, serious concerns were raised in respect of allocation of generic medical cards from a patient safety perspective, public accountability – for example significant costs incurred where we have limited audit trail. In the case of Safetynet a quick review of 50 STCs submitted for one month confirmed the vast majority of clients had medical cards in their own right,” she wrote, STC referring to special type consultations, considered by an HSE source as a particularly profitable method of healthcare provision.

For the year Burke wrote her memo, €1,390,955.63 was charged to this single generic medical card. The following year did record a marginal decrease, but despite all the increased scrutiny, €1,363,589.65 was still charged to the card. Much of these charges could be traced back to Safetynet’s method of paying its associated GPs – these GPs were treated by Safetynet as individual contractors rather than salaried employees.

This is how it worked. A GP, sometimes a trainee GP, would see patients at a Safetynet or Safetyet-affiliated clinic. Rather than be paid directly for their work, these GPs would submit claims on the K699982A medical card and then be paid a portion of these claims by either Safetynet or O’Carroll.

This method of paying GPs brought with it little transparency.

The HSE considers the needs of a private equity-backed healthcare provider

O’Carroll did discuss at the highest political level the possibility of employing salaried GPs, rather than those who would make claims on his behalf for every patient they would see. He did so with Simon Harris, when Harris was minister for health, at a late 2016 meeting also attended by HSE national director John Hennessy.

The meeting took place in November at the end of a year when €1,821,986.58 was charged to the generic medical card and when O’Carroll was still yet to resign from Safetynet. O’Carroll discussed his employment of salaried GPs as a pilot in a practice in Dublin 1, in an area of social deprivation, and suggested to both Harris and Hennessy three possible models for employing GPs rather than relying on the generic medical card.

Harris and Hennessy both indicated their preference for having organisations like Safetynet, rather than the state, employ these GPs.

Minutes taken at the meeting note that the HSE’s Hennesy had reservations about the state funding the employment of GPs in disadvantaged areas. Alongside considerations for patients, Hennessy, according to the minutes, was “considering the needs of Centric''.

The state employing salaried GPs, according to Hennessy, “may displace others, for example other GPs or private for-profit companies such as Centric”. Centric Health is a private equity-backed healthcare company that through its subsidiaries operates 46 GP practices across the country and recorded turnover of €34.56 million from June 2018 to June 2019.

Harris agreed and accepted there would be “challenges from ‘mainstream’ GPs who feel special treatment for certain areas would be unfair”.

Both Harris and Safetynet, according to the meeting’s minutes, spoke approvingly of the casualisation of general practice, using similar arguments to those made by defenders of the gig economy and zero-hours contracts. Harris “noted the advantages for part-time GPs, for example mothers of young children,” while “Safetynet agreed and said this is the same for nurses, dentists and many other healthcare professionals and that the market is definitely turning towards being flexible to customers and towards providers.”

Though Safetynet did begin moves towards employing salaried GPs, which should have brought increased transparency and decreased charges on the card, in the year following this meeting, charges on the card ran to €2,535,722.14. As the card would expire in the proceeding years, it kept getting extended by the HSE: twice in 2013, once in 2014, three times in 2015, once in 2016, once in 2017 and twice in 2018.

It was in late 2020 – in the aftermath of the Leo Varadkar leaking controversy, which tangentially involved Safetynet through its former employee Maitiú Ó Tuathail – that the HSE returned to the potential for Safetynet and its affiliates to profit from homelessness healthcare.

What does it mean to be ‘a little ambitious’?

When Leo Varadkar had to face questioning in the Dáil over his leak of a confidential GP contract to his friend Maitiú Ó Tuathail, first reported in Village Magazine, he explained he used be in intermittent contact with Ó Tuathail concerning Safetynet, for whom Ó Tuathail once worked. Former NAGP president Ó Tuathail’s part in the story, including a WhatsApp message he sent suggesting there were profits to be made in direct provision, seems to have been a cause of concern for HSE officials, given Ó Tuathail’s association with Safetynet.

After Safetynet medical director Angela Skuce drew the HSE’s attention to the “very profitable” clinic being run in the Capuchin Day Centre for Homeless People, HSE assistant national director Shaun Flanagan raised what he called the “NAGP” story.

“Dr Skuce has a line in her email that probably flags something that resonates with some of the media coverage over the weekend in relation to the NAGP WhatsApp messages which were reported,” wrote Flanagan. Flanagan also wrote, in a separate email referring to a colleague who had spoken of her desire to finally address the longstanding poor governance of card K699982A, “Some of the content of internal NAGP WhatsApps that circulated around the NAGP leakgate issue may have shocked her was my read but nevertheless it offers us an opportunity to regularise issues that have long been a concern but progress was challenging.”

So this was a chance for the HSE to finally clear up outstanding issues with this medical card. One problem for the organisation however was figuring out who was actually responsible for it. Current Safetynet general manager Fiona O’Reilly is adamant the card doesn’t belong to her charity and said she didn't know to whom it is registered . "It's not ours. I know what we use it for. We use it to prescribe medication for people who don't have a medical card. If people are using it for payments, they're not doing it under us," she said. Safetynet, she said, “uses this card specifically to access prescription medications for vulnerable homeless persons who cannot afford them”.

Assistant national director Shaun Flanagan thought otherwise. He thought the card was a Safetynet card up until December 2020. He also thought Austin O’Carroll and Kieran Harkin (to whom the card is formally registered) were still working with Safetynet. “Apparently these changes took place three years ago. You may know all this… but this was new to me,” he wrote to his colleagues in late 2020 after learning the truth. In another mail he wrote that medical card K699982A “is no longer a Safetynet card”.

One thing was clear though after Skuce’s email: “We agreed that we needed to get improved governance around generic cards,” wrote Flanagan in a December email. He also wrote what he understood to be the HSE’s aims for generic medical cards such as K699982A.

These aims seemed fair: “clarity around what a card is for”; “clarity around what is claimable and not”; “a reporting system to the person responsible for the card”. On achieving these aims however – clarity on what the card can be used for; putting in place controls and a reporting system for the €22 million medical card – this HSE assistant national director wasn’t hopeful.

“I might be a little ambitious in my understanding here,” he wrote.

¶ The HSE press office, when reached Friday evening, couldn’t confirm when they could deliver a statement, though individual HSE employees were contacted for response on generic medical cards in early May. Drs Austin O’Carroll and Kieran Harkin, as well as the Capuchin Day Centre for Homeless People, did not respond to requests for comment.

Safetynet general manager Fiona O’Reilly said the charity is “fully compliant with all legislative requirements”, including “healthcare provision and financial accountancy” and that it faces “no current issues or outstanding matters” in this regard.

One of O’Carroll and Harkin’s clinics, run by GMQ and affiliated with Safetynet Primary Care, is held in homelessness charity Merchants Quay Ireland in Dublin 8, just south of the Liffey. Banners flying outside the facility promise “a fresh start”, “an open door”, and “a helping hand”.

One May evening, women gathered outside and greeted each other with hugs. Some remonstrated with Merchants Quay Ireland staff members who would emerge from the building every now and again, sometimes to hand brown paper bags to those outside, sometimes to make a short journey of a few hundred yards up the street to check on an ongoing scene.

Just outside the adjacent Franciscan Union, a small crowd stood over a man who seemed to be in his 30s. He was out cold, lying on the street, and receiving treatment from a paramedic. The crowd chatted with the medical staff present, who’d been brought to the scene by the fire engine now parked on the footpath. One young man stopped passersby and tried to sell them a new t-shirt from a Lidl carrier bag.

An ambulance arrived to take the knocked-out man away. The fire engine pulled off, the paramedics inside exchanging waves with the crowd of eight who stayed on, chatting, their associate now on his way to hospital.

These are the people who’ve made these clinics “very profitable”. And it just was another day for them. They don’t know about the review generic medical card number K699982A will face next week, nor what kind of contributions they’ve made to its €22,404,819.52.

No one knows.